Do morals have anything to do with religion? Supernaturalists say they do. Their theory is, an action is good if God commands that it is good. Alternatively, an action is bad if God says that it is bad. So murdering is bad because one of the ten commandments says "thou shalt not kill". This kind of theory of morality is nice because it makes morals objective (have an truth value that is independent of what we think). We can resolve the differences between cultures by saying that there is only one right way of doing things, and that is what God commands. So cultures which practice polygamy (custom of having more than one wife) are wrong.

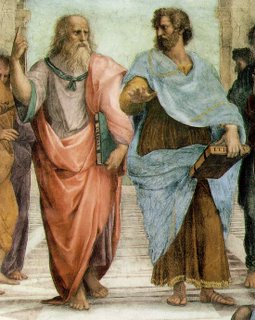

Generally, arguments which rely on the existence of God are considered bad arguments. This is because the existence of God is controversial in itself. Nevertheless, a stronger way to attack such an argument is to assume that there is a God, and show that the argument doesn't work anyway. Socrates, an ancient Greek philosopher, thus managed to show how Supernalism fails as a theory.

He asked: are actions good because God commands them, or does God command them because they are good? This question is very significant for Supernaturalism because it creates a dilemma. If it's the latter, then Supernaturalists must find another theory for what is good; if it's the former, then we can generate some pretty counter-intuitive examples as to why this cannot be. If murdering is wrong because God says it is, then God could say that torturing babies is good and then it would be! But this is absurd: we would never believe that torturing babies is good, no matter how much God said that it was. Some argue that God would not command such a thing. But what if he did?

So you don't have to be religious to be moral.

Further Reading:

- Gensler, H. J., 1998, Chapter 2, Ethics: A Contemporary Introduction, Routledge

- "Euthyphro" by Plato from The Collected Dialogues of Plato Including the Letters, Ed. Edith Hamilton & Huntington Cairns, Princeton University Press