No-one is immune to the shock of contemporary art. It strays so far from the mainstream that sometimes we can't help thinking that it might not be art at all. It's imposter art. People only think it's art, it's really something else. But if we are to judge what is and isn't art, then shouldn't we be able to come up with a definition of art? Shouldn't there be a defining feature that makes something an artwork? In other words, what makes an artwork, art?

To answer this question, we need to find something that is common to every single work of art: an essence of art. You might think "Well, every artwork is created by an artist, so something is a work of art if it is created by an artist". Unfortunately, this definition is circular:

What is an artwork? Something created by an artist. What is an artist? Someone who creates artworks. What is an artwork....

So this definition gets us nowhere unless we can define what an artist is.

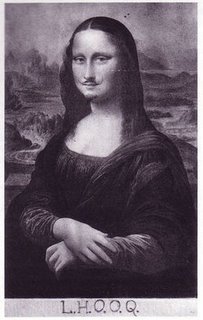

It's pretty hard to find something that is common to every piece of artwork, and yet we always seem to know what is and isn't art. How do we know? How do we know that the Mona Lisa is an artwork? Is it because it is in a gallery? That can't be right - there are some artworks that are never exhibited in a gallery, and yet they still seem to be works of art.

The quest for finding the common feature to every artwork has proven to be so difficult that some philosophers have given up entirely. Instead, they suggest a family-tree explanation of our ability to detect "art"; it's similar to the way we recognise people from families. For example, imagine that the Smith family have particularly large noses and small eyes. These features make them easy to distinguish from others. The aunts, uncles, cousins are not so easy to recognise. Some of them have the same small eyes, some of them have the particularly large nose. But once we can pick them out, we can pick out even more distant relatives, and so on. The story is the same with art. We are all well aware that Renaissance paintings are art. Impressionist paintings, however, are different because the images are blurred. But we can still recognise them because they're still painted with oil on canvas. It has now gotten to the point where we can recognise Andy Warhol's Brillo Boxes as art (although it debatable as to whether it is).

So there is no essence to art after all. It's art if it's only similar to what we traditionally recognise as art. Actually, there is one potential essentialist theory of art, and this is given by Arthur Danto. In his argument, he uses Brillo Boxes (shown above) to illustrate his point.

Brillo Boxes represents the edge of art. If it was on the family tree of art, it would be the most distant relative. It is completely on the border because it is indistinguishable from a stack of Brillo Boxes at a supermarket. The boxes are actually made out of plywood, and were painted by the artist, but this does not concern us because we are interested in finding out how we can distinguish art by just looking. There is one crucial difference between Warhol's boxes and the boxes at the supermarket: behind Warhol's painted boxes is a theory of art. In fact, behind every single work of art is a theory of art. Even behind the cave paintings at Lascaux. And this, Danto argues, is the essential feature of art. When we see the Brillo boxes at the supermarket, we see a stack of Brillo boxes. But when we see Warhol's Brillo boxes, we see something else. There is something which is much more intriguing and exiting about the artwork, and that is it's conceptual component.

It's a neat theory because it suggests that there is such a thing as art, and it gives us the ability to determine what is and isn't art. The only problem with Danto's theory is that it pre-supposes that Brillo Boxes is an artwork. Brillo Boxes is a work that quite a few people would protest as not being art. I'll leave this up to the reader to decide.

It is important to note that just because it is art, it is not necessarily good art.

Further Reading:

- Danto, A., 1964, "The Artistic Enfranchisement of Real Objects: The Artworld", Journal of Philosophy 61, no. 19, pp. 571 - 84

- Kennick,W, 1958, "Does Traditional Aesthetics Rest on a Mistake?", Mind 67, pp. 317 - 334